Comments

“Superbly curated and impressively recondite, these essays are as provocative as they are wide-ranging—from the weird that is Sun Ra to African Apocalypse to the Wakanda homeland of Marvel’s Black Panther … and for someone like me, a child of the African diaspora, and a full-out futurist geek, it is indispensable.” – Junot Díaz, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007)

“Whether it’s musician Sun Ra, American SF writer Octavia Estelle Butler or the Ghanaian AfroCyberPunk writer Jonathan Dotse, this issue of one of North America’s most lively journals is crammed with wonderfully wide windows opening onto African and African-inspired writing and music around from the world. You really don’t want to miss this one!” – Samuel R. Delany, author of Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders (2012)

“Franz Fanon opened his seminal book The Wretched of the Earth with the bold statement: ‘Decolonization is the veritable creation of new men.’ There is something intrinsically science fictional about the new beings and temporal disjunctions in the colony, the postcolony and the trajectories of uneven development. In this special issue of Paradoxa, guest editor Mark Bould has brought together an outstanding group of critics to think through the conjuncture of Africa and science fiction really for the first time with proper rigour and critical sophistication. The collection contains Bould’s essential outline of the African re-functioning of science fictional tropes, and some brilliant interventions into the history of comics, colonial adventure fiction and film. This heady brew is rounded off with John Rieder’s powerful reflections on the weird and wonderful world of Sun Ra’s ‘occult jazz’ experimental mythology. This collection breaks new ground: the horizon of science fiction studies has just been expanded again.” – Professor Roger Luckhurst, Birkbeck, University of London, author of Science Fiction (2005).

Reviews

SFRA Review, review of “Africa SF”

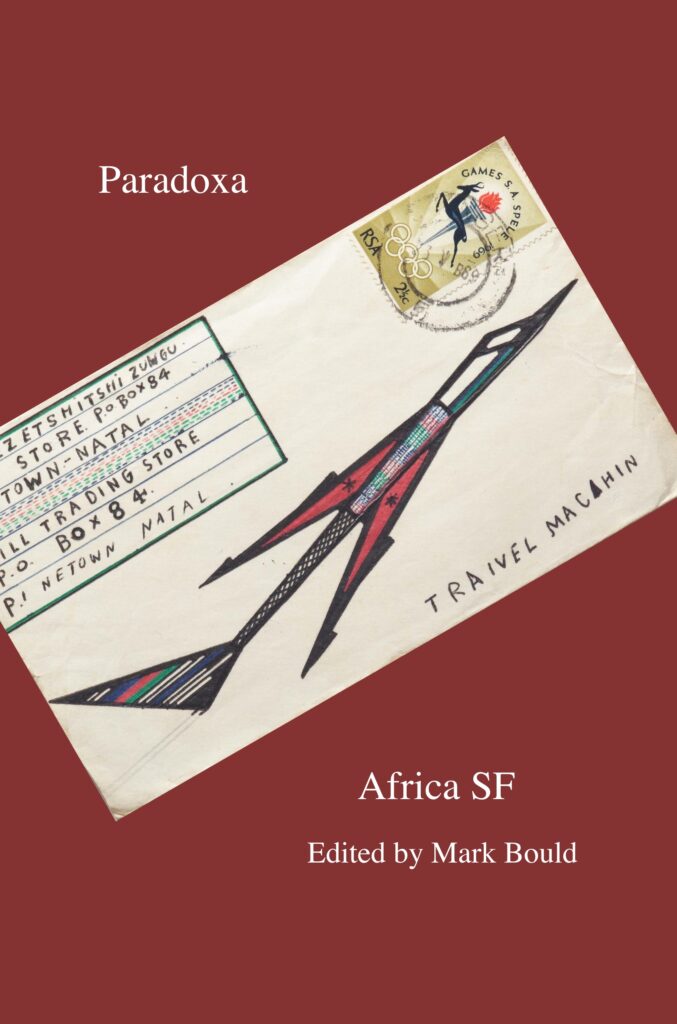

Paradoxa: Africa SF

Hugh Charles O’Connell

Mark Bould, editor. “Africa SF.” Special Issue of Para- doxa, no. 25

AS MARK BOULD’S introduction to Paradoxa’s special issue “Africa SF” makes clear, the western-derived concepts of “Africa” and “SF” are deeply imbricated. The mandate of “Africa SF,” then, is to force us to think not only about the concept “Africa” as constituted by SF, but also of SF as constituted by Africa. Indeed, Africa was at the center of the development of SF from its start, whether as the ‘otherworldly’ space of adventure for exploitative colonial projects and lost race tales or as a place for early African American anarchists and socialists to project their utopian visions (9). Across the his- tory of SF, then, Africa is an unstable sign, and if it is this instability that so many earlier western SF authors sought to contain, it is this same instability that African and African diasporic authors and their critical interlocutors now seek to prise open in the name of new fu- tures and futuricities, in the form of what Eric D. Smith has re-dubbed SF’s “New Maps of Hope.” And if there is one thread that runs across the various articles, interviews, and reviews that comprise this expansive issue, it is the Afrofuturist and African futurist possibilities that inhere despite (or in some cases because of) the very crisis conditions that often form the hegemonic valence of neoliberal discourses that take Africa as their object.

To give some conceptual order to this project, the issue “situates African sf in three broad contexts: the history and recent development of the genre in Africa; sf produced within the African diaspora; and the treatment of Africa in sf ” (7). The Africa or Africaness that ties these disparate foci together is multivalent, and it is among the issue’s strengths that it takes a discursive approach rather than trying to forge a unifying gesture that would run roughshod over national and ethnic differences. Outside of this three-pronged conceptual-organizational structure, the issue takes a pleasantly free-wheeling approach when it comes to content. It comes as no surprise to anyone familiar with Mark Bould and Sherryl Vint’s influential “There is no Such Thing as Science Fiction” that the issue’s approach to genre is wide and inclusive; it treats the borders between science fiction, fantasy, and horror (among others) as rather porous. Moreover, the dispersal of this discursive notion of the SF genre across a wide swath of media allows for a substantial thick description of “Africa SF” to emerge through individual articles that focus on everything from film, mass market comics, literary graphic novels, and SF topoi in literary fiction, to explorations of new avenues for creative-critical projects in the art world, music, and written genre SF.

The shortest of the three conceptual sections is dedicated to contemporary visions of Africa from within western SF (and shortest for good reason, given how long western SF writers have made Africa the object of their colonizing gaze). Here, Neil Easterbrook ex- amines the transformation of the western SF tropes of the evolution narrative and African colonial adventure novel in Ian McDonald’s Chaga saga. Paramount for recovering these most imperialist and racially susceptible narrative forms for Easterbrook is the way that the Chaga saga foregrounds the European protagonist’s alienness within the African landscape, splinters the journalistic-consumptive gaze through an increasingly multi-focal narrative approach, and represents the new Chaga(alien)-African hybrid evolutionary transformation as a counterforce to neoliberal economic developmentalism. As Easterbrook argues, “In the Chaga saga, Africa is sf” (199). This stance allows for “a projective thought experiment on the inevitability of change, and on the possible consequence of change” within the global world-system (200). Indeed, with this utopian, inflationary stake, his reading strikes a tone that resonates with other articles that focus on SF production from within Africa, allowing for a more provocative contrapuntal reading across western and African SF, rather than a merely oppositional or contrasting approach.

Many of the articles focusing on SF produced within Africa likewise counterpoise the contrasting discourses of western dystopian apocalypse and Afro-utopian possibility. To borrow from Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s article, they work alongside already existing notions of Afrofuturism to produce a corresponding “African Futurism’ in order to locate an African sensibility in the imagining of African futures” (113). In this light, following the lead of Ghanaian cyberpunk novelist Jonathan Dotse, Lisa Yaszek re-reads the purportedly dystopic and apocalyptic spaces of African modernity as simultaneous progenitors of a utopian surplus. Reading across these sites of local possibilities, Yaszek uncovers with- in the filmic and literary SF coming out of Africa new “spaces of uncertain potential that contain the seeds of many different futures” (48), which then combat the western imposed ontology of crisis that threatens to engulf the continent.

Likewise, reading across three African SF novels – Mohammed Dib’s Who Remembers the Sea (1962), Sony Labou Tansi’s Life and a Half (1979), and Ahmed Khaled’s Utopia (2009) – Mark Bould limns a trajectory “from anti-colonial struggle to neoliberal immiseration” (19). Yet this trajectory is not presented deterministically, as Bould still finds reason to be hopeful in the possibilities presented by the Arab Spring as a popular political formation that, although anticipated by texts like Khaled Towfic’s Utopia, also counters their pessimistic limits. In doing so, he offers a counter-narrative to the afropes- simism that animates the countering ideals of the neoliberal futures industry and so much of postcolonial studies in the figure of very real, present political movements. This focus on the precariousness yet possibility of material political reality is similarly found in the two essays on Lauren Beukes by Malisa Kurtz and Marleen Barr, which focus on the effect of the actually-existing legacies of apartheid in South African SF. Lest we should make a new fetish out of Africa as a reified site of a banal utopianism, Kurtz, Barr, and Bould remind us of the all too real and all too actually-existing entrenchment of neoliberal capitalism within many national governments, as well as the shifting currents of possibility that arise within these contexts. African SF’s most salient vo- cation, then, is to mediate this conjuncture in order to reveal its animating and constricting contours.

Of equal weight to the SF coming out of Africa is the examination of the SF of the African diaspora. One of the most surprising and intriguing aspects to emerge from this cross-section of articles is the dialogue between superhero comics, SF, and the racial politics of the post 1950s US. De Witt Douglas Kilgore’s meticulous reconstruction of the disjunctive development of Marvel Comics’ most significant African superhero, the Black Panther, and his fictional African techno-utopian nation of Wakanda, dovetails brilliantly with Gerry Canavan’s analysis of the impact of superhero comics on Octavia Butler’s Patternist series. The radical and subversive Afro-utopianism of the Reginald Hudlin helmed Black Panther that was so slowly and precariously built up and redeemed from decades of tokenism and then subsumed by the Disney Corporation’s buyout of Mar- vel Comics makes for a fascinating intertextual dialectic with Canavan’s analysis of Butler’s deconstruction of the superhero, where the superhero is posited as a pure emblem of force that lies outside of ethics, and is thus analogous to the concept of force developed through Hart and Negri’s conception of Empire. These two articles form a reminder of the principle that binds all of the articles across the issue, whether implicitly or explicitly, that the coupling of “Africa SF” is rather something of a negative dialectic. That is, there is an unresolved tension as both concepts ultimately do violence to one another when brought into dialectical contact. There is no simple resolution in sight, either in the political-material realm from which these sf texts stem, or in the works them- selves as they mediate the tension between late capitalist suture or systemic collapse that makes even the most local and remote crisis a potentially global-altering event.

As Bould avers, there is a danger in making Africa the focus of intellectual and scholarly pursuit, and this may be doubly so under the rubric of SF studies, given its imperial technoscientific auspices. Since SF is a “product of colonial and neo-colonial powers,” we need to be cognizant of what happens to African texts when we subsume them under the category of SF: “Can they be understood as sf without misunderstanding or misrepresenting them? To what extent is claiming them for sf a violent misprision? To what extent is it just another colonial appropriation?” (17). Indeed, the greatest intellectual merit of these articles, whether taken individually or collectively, is that they refuse to resolve this tension. Rather than asserting the final word and thus quelling the intellectual contact zone that is Africa SF, this wide-reaching volume opens up a new range of possibilities for future projects that recognize both the intellectual difficulties and the rewards of exploring the co-determining transformations of SF through an African-futurist lens and African futurity through an SF lens, whereby instability and indeterminacy become allies of utopian possibility.